Editing: Temporal Connections

Staging Dialogue

Welcome the DESN3020 Cinematics course material (courtesy of George Brown College). The subjects of this posting is editing to create temporal connections and staging dialogue.

Editing: Temporal Connections

Film History moment:

- 1920 - Lev Kuleshov performs a now famous experiment that demonstrates that the meaning of shots in sequence can be created entirely through editing.

- Here we see a close-up of a male actor’s expressionless face as a reaction shot in 3 different sequences.

- We see the actor “reacting” to:

- a bowl of soup

- A child in a coffin

- A woman lying on a sofa

- Audiences marvelled at the actor’s sensitive performance in every instance, even though it was the same close-up shot being used!

You can see the Kuleshov footage with an overview here:

Basically, viewers tend to bring their own emotional reactions to a sequence and then attribute those reactions to the actor on screen.

While the editing process can have a powerful impact, in most narrative films shots are rarely neutral building blocks pieced together as Kuleshov used them.

Shots have been composed to tell a story and convey a feeling according to the script.

Each shot, together with soundtrack, contains narrative and graphic info that predetermines key editing decisions – like length and order of shots

- This view of editing emphasizes director’s and writer’s role in shaping storytelling logic that gives the editor a basis to work from.

- Storytelling logic refers to structure of shots, sequences and scenes.

- Structure controls the order in which info is given to the viewer.

The order in which info is given to the audience is as important as the information itself!

Since structure in cinematography can be conveyed in a storyboard in ways that a script just cannot, the visualization process can be considered part of the writing and in the end the editing process as well!

The Narrative Impulse – from E.M. Foster’s definition of a plot

- If we state that “The King died and then the Queen died” we don’t have a plot

- If we say “The King died and the Queen died of grief” we have described a plot because there is a causal connection.

- In any story, this cause and effect relationship is the underlying scheme that involves the reader/viewer.

- It achieves this by asking the reader/viewer to make the logical connections between events.

- Foster’s example above is simplified to make a point, doesn't show us how the author could reveal the relationship between King and Queen.

In fiction, cause and effect often set up as question and answer scheme

- Encourages our participation

- Cliff-hanger ending in serialized stories (instalments in a larger story) where answers are withheld to create suspense is an example of most exaggerated way of exploiting this device

- Questions may be answered through the accumulation of much information over time while others can be answered shortly and quickly after being asked

Continuity editing is based on these kinds of question and answer schemes, usually called connections.

Following are 3 most basic types of connections found in continuity editing:

- Temporal connections – cut from a man dropping his drinking glass in one shot to the glass breaking on the floor in the next shot.

- Spatial connections – cut from a wide shot of the White House to a recognizable detail of the White House in a closer shot (like the front door)

- Logical connections – we cut from a wide shot of the White House to a shot of the President seated in his office. We don’t need a temporal or spatial connection if we recognize that the President would be seated inside the White House (for example).

We can think of these as background connections that establish environment, but we can also use them to shape the plot and dramatic content as well!

Narrative Motion

- Nearly all editing strategies in narrative film are devised to set up a framework of expectations in a series of shots. The result is narrative motion.

- This way of arranging shots is fundamental in film editing.

Q&A Patterns

- Simplest Q&A editing pattern requires only 2 shots:

- Shot of actor looking offscreen

- Shot of thing actor was looking at

- Patterns not limited by length, may take dozens of shots to complete a Q&A cycle.

- Some of the best Directors are admired for the way they develop these patterns that challenge the viewer

Conext

- Meaning of any given Q&A pattern can be further extended / modified by changing the context that frames it.

- In the example we started with, our understanding of the man’s reaction to the bowl of soup, coffin, and lady is framed by our assumption that the man is sincerely moved in each scene.

- If a new scene were added that lets us know he is faking his reactions, then we will interpret the whole sequence differently

Using the patterns

- Interesting compositional ideas are usually the result of inventive narrative techniques rather than boundary-pushing visual techniques.

- The next few examples show how narrative context and Q&A pattern determine how we “read” a scene...

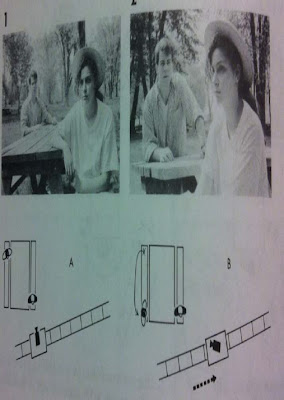

Example 1:

Our scene takes place in the woods on a summer day. Laura is looking for Tom. We have not yet seen Tom, so we don’t know what he looks like.

- Shot A: Laura enters the woods (Q: Where is Tom?)

- Shot B: Laura stops short a few yards from a clearing (Q: What has she found?)

- Shot C: Tom and a girl are lying naked on a blanket in the clearing (A: Laura has found Tom...BUSTED!)

|

| Example 1 |

Example 2:

- Shot A: Laura enters the woods (Q: Where is Tom?)

- Shot C: Tom and a girl are lying naked on a blanket in the clearing (Q: Will Laura find Tom?)

- Shot B: Laura stops short a few yards from a clearing (A: Laura has found Tom!)

Here, if we prolong the time before Laura arrives, the viewer would share a secret with the film-maker – we know Tom is nearby in a compromising position.

- Placing an answer before a question creates suspense

|

| Example 2 |

Example 3:

Change the narrative context again!

- Shot C: Tom and a girl are lying naked on a blanket in the clearing (A: Tom is Here)

- Shot A: A girl enters the woods (Q: Is this Laura?)

- Shot B: Laura stops short a few yards from a clearing (A: This is Laura!)

By having the compromising position in the opening shot, we've established a suspenseful situation.

- Editing patterns and the narrative context do not necessarily lay the events of a story out in simple chronological order

|

| Example 3 |

The Limits of Clarity

Because Q+A storytelling techniques frequently relate info in a roundabout way, this indirectness may be confusing to others in a screenplay, shot list or storyboard.

Avoid unusual Q+A patterns because it will be difficult for an audience to follow.

If an establishing shot merely shows us what we already know and does little to raise our expectations or contribute to narrative motion then it could in the end be less effective than a more challenging sequence of establishing shots

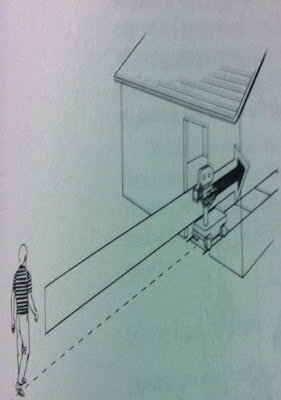

Camera Cutting vs Coverage

A fully-developed storyboard can show a director all the shots needed for a scene.

In CG productions, we “Cut in the Camera” as some film directors also do.This means that the camera (shot size and angle) is specified in the storyboard.

This cuts down the amount of footage needed as the director only shoots the action from the specified camera.

Often in film, directors shoot to get “Good Coverage” of the action, but this results in a lengthy editing process – and lots of footage. This is too expensive to do in CG.

CG production (films, tv, cutscenes) tries not to create more footage than is specified in the storyboards. It is too expensive (artists time, rendering time).

- Smart planning and pre-visualization means less work in the long run!

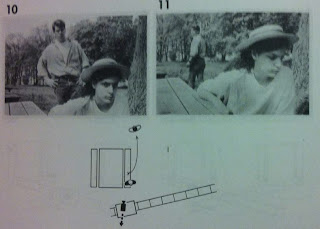

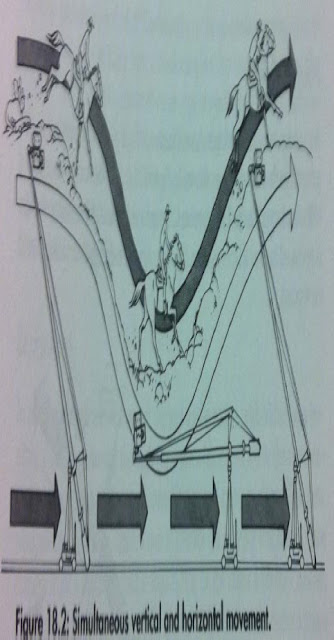

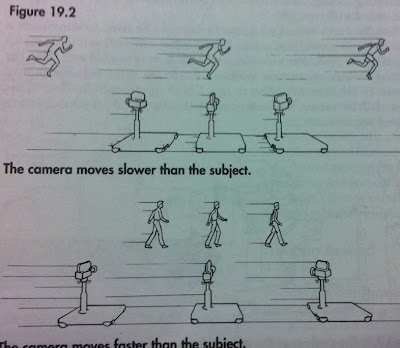

Cutting On Movement

Let’s say we have a boy jumping over a hedge and we want to decide where to insert a new shot of the action.

3 options:

- Cut to a new shot at the point where the boy reaches the hedge, begins to jump

- While the boy is jumping

- After the boy lands

|

| Cutting on a movement. |

These are all 3 acceptable edit points, but in Continuity style, convention would be to cut before of after the boy has left the ground.

- Tends to hide the cut, making the transition to the new shot invisible!

- Exact point of the cut is dependent on subject’s and editor’s sense of movement.

- Cutting on action is found in almost all types of sequences – if the subject is lifting a drink, or merely moving his or her eyes, or running from a huge rolling ball in the Temple of Doom.

- Mindful filmmakers will stage action so that it will overlap an edit point - in animation, the action should repeat

- last 6 frames of the outgoing (first) shot should have the SAME action as the first 6 frames of the incoming (second) cut (overlapping action)

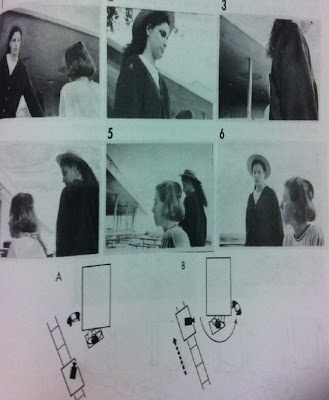

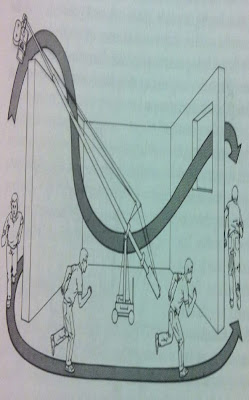

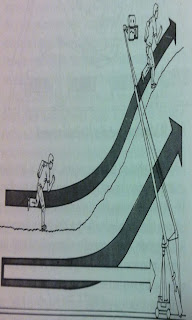

Exits and Entrances

When the subject of a shot moves into or out of the frame, common practice is to make the cut while the subject is still partially within the frame.

- The effect on screen is to make the cut smoother and speed up the flow of action.

- Here we see the position of a subject in an outgoing and incoming shot.

|

| Exit and Entrances |

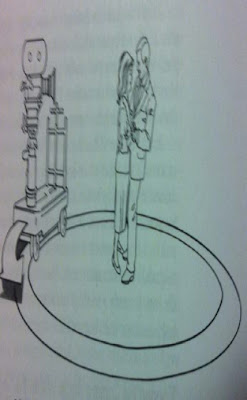

Clearing the Frame

Alternative to cutting on movement to join different angles of the same object

- Subject is allowed to exit the frame before the cut to the next shot.

- Customary to hold on an empty frame of the outgoing shot for a moment

- Can still have other action the frame while this “hold” is happening

|

| Clearing the frame |

Can look at this in 2 ways

- A method of joining shots of the same subject in different backgrounds – Similar to dissolve, it indicated the passage of time.

- A substitute for the cut on action so that the incoming and outgoing shot represent continuous time.

Useful if you are afraid of making a continuity error – almost impossible to do so with this technique, it can even be used to join shots on opposite sides of the Line of Action!

|

Clearing the frame

|

One last strategy:

- The outgoing shot ends with the subject clearly in the frame.

- The incoming shot begins before the subject appears and holds on a clear frame for at least a second before the subject enters

- note: film moves at 24 frames per second. Illustrations below are not frame accurate

|

| Outgoing/Incoming |

Editing and Visualization

- The value of knowing conventional editing techniques – gives you a good starting point when visualizing (storyboards etc)

- Staging is made easier by being aware of the types of movement that provide a good opportunity for cutting shots.

- In any scene, you will visualize how long certain action should be viewed before moving on to another shot.

- Don’t think of these rules as overly restrictive. They can be broken.

- The value is being able to visualize the camera setup for an entire sequence, allowing focus on the dramatic needs of the scene!

Staging Dialogue

The goal: honest expression of human relationships and presentation of these relationships to viewers.

The challenge: the ability to predict in 3D space what will look good on a 2D screen.

The spatial approach is made up of 5 basic areas of focus:

- Staging stationary actors

- Staging moving actors

- Using the depth of the frame

- Staging camera movement

- Staging camera movement and actor movement together

Some basic conventions to be aware of:

- Frontality – Subject of a picture tends to face the viewed head on. “Cheating out” actors tend to face the camera more than each other directly.

- The Master Shot – one shot that is wide enough to include all actors, sometimes part of a series of shots, sometimes the only one necessary

- The Sequence Shot – When the master shot is a moving shot and moves fluidly with a Dolly throughout the course of the scene.

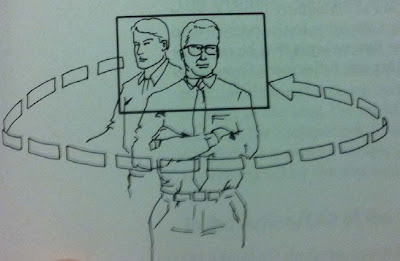

- Shot Size and Distance – Medium 2-shot is the tried and tested way of covering 2-person dialogue (perhaps even over-used) and allow body language to be shown.

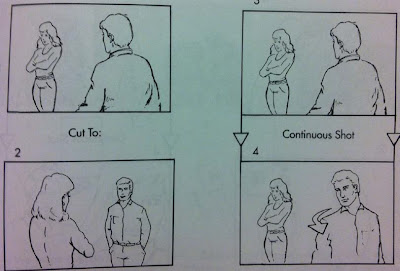

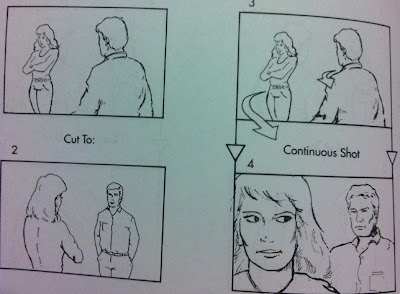

- The Shot, Reverse Shot pattern – When actors are seen in alternaing close-ups (remember continuity!).

Some basic conventions to be aware of:

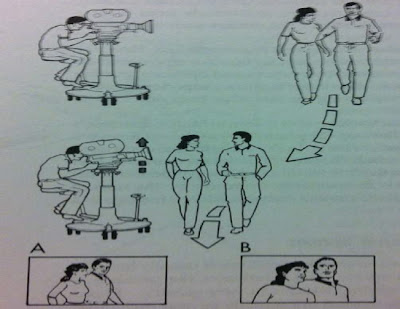

- Sight Lines and Eye Contact – The closer the sight line is to the camera, the more intimate our contact with the actor. Direct eye contact with the camera though can be quite startling

- Once you’re familiar with the psychological and dramatic implications of sight lines and eye contact, you can make subtle shifts for dramatic emphasis in a scene.

|

| Sight Line and Eye Contact |

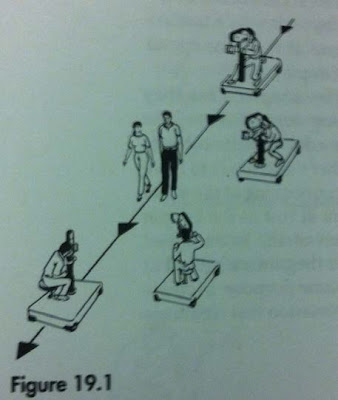

Staging with “Letter Patterns”

- The system we’ll be looking at uses 2 categories to describe actor placement:

- Pattern: 3 basic letter patterns: “A”, “I” and “L”. These are the letters that grouped actors resemble from above.

- Position: the direction the actors are facing within a pattern. Can be many positions for any given pattern.

|

| A, I and L Patterns |

The “I” pattern for 2 players is the basic building block of this system.

- The “I” pattern is even found within the “A” and “L” patterns when we are isolating 2 characters in a shot out of a larger group or staging formation

|

| Dialogue Patterns |

Position 1: Face to Face

- Most basic conversational positioning.

- Allows for powerful subject oppositions.

- Don’t see much facial expression unless the framing is very tight

|

| Face to face. |

Position 1 – OTS

- Used for shot, reverse shot pattern.

- Can isolate the speaker by framing tightly, blocking off 1/3 – 1/2 of the back of the other character’s head.

- May be a logical follow up to shots we saw previously

- Can experiment with low angles as well to make “Over the Hip” shots

|

| OTS |

Position 1 – Low Angle Reverse Shot

- “Over The Hip Shot”

- Dynamic, put characters in adversarial positions.

|

| "Over the Hip Shot" |

Position 2 – Shoulder to Shoulder

- Frontal positioning offers more options since we see front or profile of both actors in same shot.

|

| Shoulder to shoulder |

Position 3 – 90 Degree Angle

- Compromise between Shoulder To Shoulder and the Parallel arrangement of Position 1

- Can put one player in profile while allowing the other to be frontal

Other positions

- There are many other positions to experiment with.

- The following are all examples that create tension.

Staging Dialogue for 3 subjects

Difference between “A” and “L” Patterns

- Not always easy to determine which applies since characters will not always be in precise patterns.

- General rule: if 2 characters are facing the other player and the 2 characters frame the other, then this is an “A” pattern.

- If the 3rd characters is lined up outside the other 2 characters, this in an “L” pattern.

- This aspect of staging is called “Opposition”

- We’ll look at some examples of it next...

|

| Difference between “A” and “L” Patterns |

|

| Examples of “A” Patterns |

|

| Examples of “A” Patterns |

|

| Examples of “L” Patterns |

|

| Examples of “L” Patterns |

|

| Examples of “L” Patterns |

|

| Examples of “I” Patterns |

Examples of In-Depth Staging

- Still uses an A-pattern here, line of action established between man and 2 women.

- Can still choose shots that respect the 180 rule to explore what’s going on between these characters

|

| In-Depth Staging |

- Obviously there are many more positions for characters and cameras to experiment with, and all could lend some meaning or imply something about your scene if you set it up thoughtfully.

- Feel free to experiment with what will work best for you and don’t be afraid to push the boundaries!

Staging Dialogue for 4 or more subjects

- Still use the same A, I and L patterns

- However, as the number of characters grow, so do the options for how to frame group or individual shots within this larger set of characters.

By the numbers:

- In a scene with 5 characters there are:

- 5 possible CU

- 9 possible 2-shots

- 6 possible 3-shots

- 1 possible master shot

- (or 27 different shots possible)

|

| Here we see the line of action established between 2 principal characters in a group. |

Here we see what happens if 3 key characters share dialogue equally

- The A pattern applies and we can position the camera accordingly

- Even the A pattern, as we now know, is reduced to blocks of I patterns when determining the line of action

|

| A Pattern |

Here we see what happens if 4 key characters engage in the scene.

- Multiple lines of sight = multiple lines of action.

- Limit yourself to a few key setups.

|

| Multiple Lines of Sight |

While it’s easy to visualize this from an aerial view (as we just have) it can be more difficult to do so from a shot framing perspective.

Some examples follow

|

| A Pattern |

|

| L Pattern |

|

| In-Depth Frontal Positions |

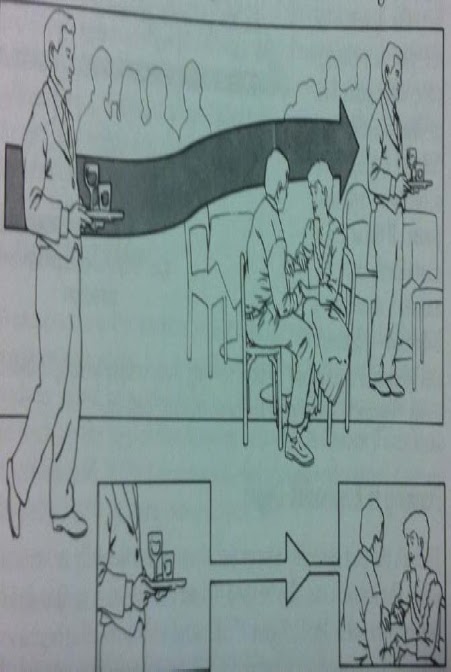

Crowds and Large Groups

2 basic approaches:

- Camera is either in the crowd looking out or outside the crowd looking in.

- Shots taken within the action are usually taken from a wide or normal lens

- Shots taken from outside the action are usually taken with a telephoto (zoom) lens.

- In CG, we simulate different lens types and focal lengths, so it’s important to understand how these affect a scene.

Comparison: Normal Lens within the action vs Zoom lens outside the action

|

| Normal Lens |

|

| Zoom Lens |